What the Solar Parker Probe Can Tell Us About the Sun and Space Weather

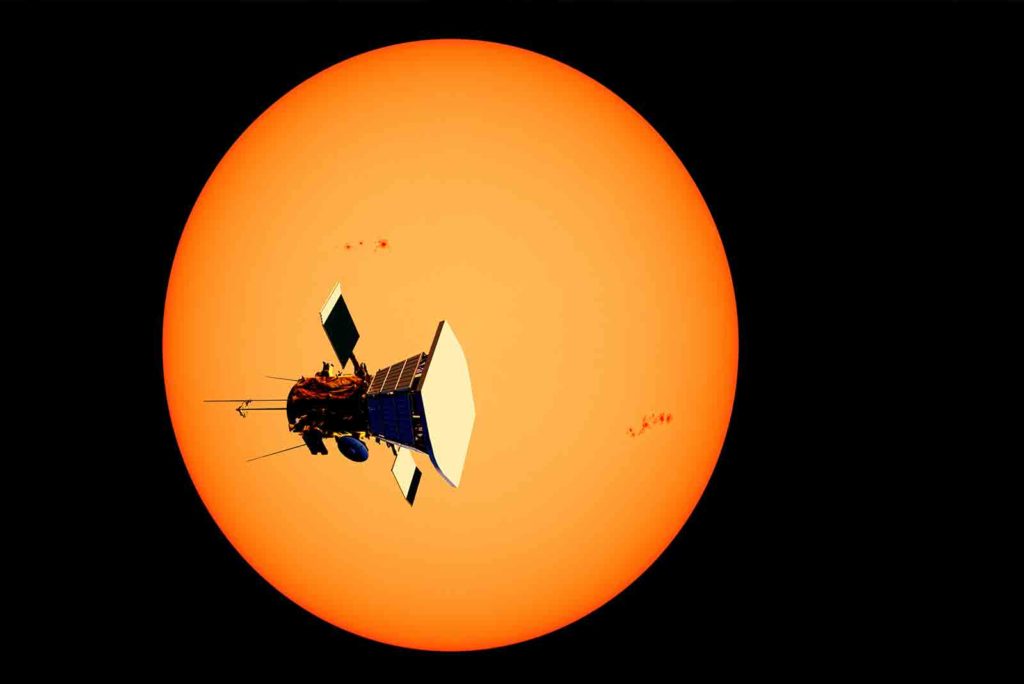

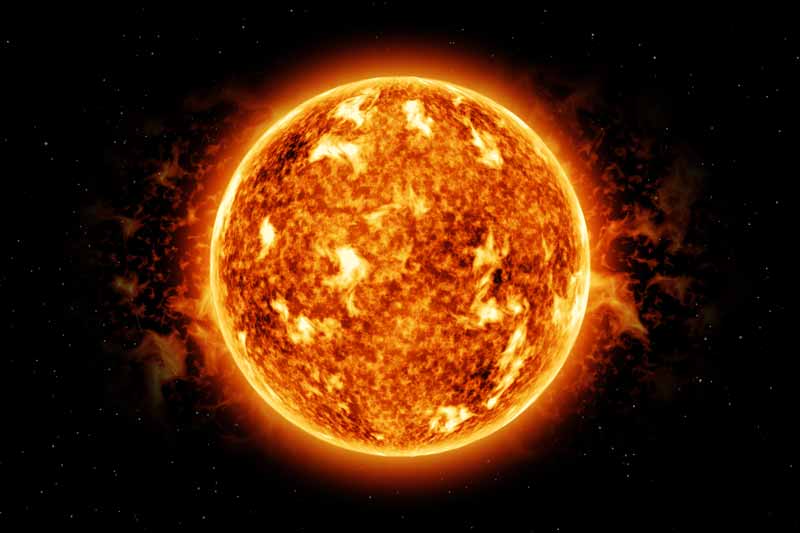

Fresh off its launch in August 2018, the Solar Parker Probe—a bold NASA initiative to touch the sun—is plunging toward the inner solar system on its mission. Come 2025, the probe will endure furnace-like temperatures as it swoops through our sun’s outer atmosphere, marking the first time humanity has ever been up-close-and-personal with the sun.

Fresh off its launch in August 2018, the Solar Parker Probe—a bold NASA initiative to touch the sun—is plunging toward the inner solar system on its mission. Come 2025, the probe will endure furnace-like temperatures as it swoops through our sun’s outer atmosphere, marking the first time humanity has ever been up-close-and-personal with the sun.

The Solar Parker Probe is the latest effort to better understand the sun. The spacecraft’s observations will help answer longstanding mysteries about how particles and energy stream away from the sun, and provide new data to help us forecast space-weather events that could affect us on Earth.

Another puzzle it could help resolve: why the sun’s outer atmosphere, called the corona, sears at nearly one million degrees Fahrenheit, while the solar surface mildly blazes at around 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit (5500 degrees Celsius).

“There are quite a few things we don’t yet understand about the sun, which is somewhat ironic because it is the closest star,” said Andrew Gerrard, a professor at the New Jersey Institute of Technology and the director of the Center for Solar-Terrestrial Research.

Scientists eagerly await the new era of sun research that is nearly at hand.

“The Parker Solar Probe launch was very exciting,” said Dana Longcope, a professor of physics at Montana State University. “I’m looking forward to some great discoveries.”

Our Knowledge of the Sun: A Quick Overview

Over human history, the sun has inspired awe and wonderment. Ancient cultures deified this unknown, bright circle in the sky, linking it millennia ago to the creator god Ra of the Egyptians, for instance, and the torch-bearing sun goddess Wuriupranili of the Aboriginal Australians.

Over human history, the sun has inspired awe and wonderment. Ancient cultures deified this unknown, bright circle in the sky, linking it millennia ago to the creator god Ra of the Egyptians, for instance, and the torch-bearing sun goddess Wuriupranili of the Aboriginal Australians.

Multi-generational, society-level engineering projects that marked solar movements across the sky, like Stonehenge in England, further demonstrate the utmost regard with which humankind has held the sun.

The sun does indeed hold powerful sway over certain events on Earth. It provides the heat that drives much of our weather and climate, along with the critical energy at the core of nearly all of nature’s complex webs of life. The growth of scientific research allowed us to comprehend just how the sun delivers its life-enabling luminance, not to mention our ability to transform its rays into energy through solar panel technology.

Key moments in our understanding have included the discovery of sunspots, following the invention of the telescope in the first decade of the 1600s CE. The famous Italian astronomer Galileo was among the first to record these puzzling, blemish-like features on what had been presumed up to then to be a “perfect solar orb,” Gerrard noted.

More detailed studies of the sun’s nature continued especially in the 19th century, when researchers realized that dark lines in the visible bands of colors from the sun also appeared when heating gases on Earth in laboratories. These so-called Fraunhofer lines — named after Bavarian physicist Joseph von Fraunhofer — offered, through a revolutionary technique known as spectroscopy, a way to infer the sun’s composition.

“These first spectroscopic studies,” said Gerrard, “were certainly important.” (For the record, the sun is about 90 percent hydrogen and 9 percent helium, with a trace of heavier elements.)

Nuclear physics in the 20th century unlocked the source of the sun’s energy: the fusion of the hydrogen atoms, made possible by the conditions at the sun’s core, where the temperature is 27 million degrees Fahrenheit (15 million degrees Celsius) and the pressure is approximately 250 billion times that on Earth’s surface. [Read more: Dissecting a Sunbeam]

Despite extensive efforts, fusion has remained unattainable for sustainable energy production, though the sun offers plenty of opportunity for solar power, like with Community Solar. In just one hour, for example, the sun delivers more energy in the form of sunlight than humankind consumes in a whole year.

An Intertwined Planet and a Star: The Earth and the Sun and the Potential Impact of Space Weather

A deeper connection between the sun and the Earth, beyond just light and heat, also started to emerge by the mid-1800s.

A deeper connection between the sun and the Earth, beyond just light and heat, also started to emerge by the mid-1800s.

The detailed recording of sunspot numbers and locations on the sun pointed to an approximately 11-year cycle of waxing and waning activity. Remarkably, scientists realized that this pattern matched that of varying geomagnetic activity, first documented by naval and merchant fleets relying on compasses for maritime navigation in the 1830s. This terrestrial-solar connection has continued to drive investigation even today with the Parker Solar Probe.

Our star is, by its nature, inconstant. It flings out bursts, called solar flares, that flood the space Earth passes through with tangled magnetic field energy and charged particles. Although mostly deflected by our planet’s magnetic field, some of these particles enter the atmosphere, primarily at the poles, energizing molecules in our air and producing aurora, better known as the Northern and Southern Lights.

These pretty celestial displays can distract, though, from the true hazards posed by this “space weather.” Solar radiation can damage satellites and endanger astronauts during spacewalks. Electrical currents induced in transmission lines on the ground can even trigger grid failures, most spectacularly in 1989, when six million people across much of Quebec lost power for nine hours.

Yet, our modern civilization has so far been fortunate when it comes to space weather. Reports have modeled the dire consequences if another Carrington event — among the most powerful solar outburst ever recorded, back in 1859 — happened today. Back then, telegraph systems failed, human operators received shocks, and office papers lit on fire from thrown sparks.

Some 170 years later, our highly electrified and technology-reliant global society is now more vulnerable to an extreme space weather event. The damage could easily reach into several trillions of dollars, with cell phone communications, the Global Positioning System (GPS), and other aspects of modern life highly disrupted, potentially for months or years.

Rudimentary forecasting systems enabled by dedicated sun-observing spacecraft offer a three-day outlook, published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center. But experts agree much more needs to be done to improve forecasting and resilience against a repeat of the Carrington event.

“Space weather is, in my opinion, very much in its infancy,” said Gerrard. “Though much of the past 50 years or so has been spent understanding the extent that space weather plays in our technological systems, its only recently that ‘real space weather forecasts’ are coming to the forefront of the national attention.”

Research Continues

Enter the Parker Solar Probe. It will improve our understanding of the dynamics involved in producing space weather, in particular, the transport of energy from the sun into the corona and out into particles streaming from the sun, dubbed the solar wind.

Enter the Parker Solar Probe. It will improve our understanding of the dynamics involved in producing space weather, in particular, the transport of energy from the sun into the corona and out into particles streaming from the sun, dubbed the solar wind.

“There are a number of questions related to how energy from fluid flow and plasma waves becomes heat in the solar wind,” said Longcope.

The Parker Solar Probe will come within approximately 3.83 million miles (6.16 million kilometers) of the sun’s surface—seven times closer than the nearest encounter on record, accomplished by the Helios-2 probe in the 1970s.

Although the Parker Solar Probe will travel through a region of space with temperatures exceeding one million degrees Fahrenheit, the probe’s protective heat shield will warm to “only” 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit (1,400 degrees Celsius). This is because of the low density of material in the fringes of the sun’s atmosphere, meaning little heat transfer to the probe will actually occur.

While braving these areas should yield key new insights into our sun, studies are also improving with regard to other stars. Long-term measurements of changes to their brightness and modeling of their evolutions are offering firm bases for comparing our sun’s behavior to its stellar cousins.

A full reckoning of the sun and its capacities for both Earthly health and harm will depend on these comparative studies down the road.

“Of course, most of our understandings of stars came from detailed observations of the sun,” said Longcope. “But they are starting to pay back.”